Last week, my 8-year-old daughter performed an original song on ukulele in front of a crowd of mostly strangers (who turned out to be supporters) in a coffee shop. Her music school offers occasional recitals in the form of open mic nights, and after just six weeks of taking music lessons, Ryn decided she was ready to perform a song she wrote. After making the decision a week prior, she proceeded to invite everyone (mostly adults, a couple teenagers who babysit her, and one of her best friends) to come see her play. Instantly, I felt nervous on her behalf. My child had anxiety about saying two sentences in her second grade musical program on the weather; how in the would could she sing and play an instrument in front of people she’d never met?

The night before her performance, for which her uncle, aunt, and cousin would now be in town to see, she complained of not being able to sleep and she didn’t know why. Of course, my husband and I suspected the looming moment on stage was enough to keep someone up tossing and turning. Looking back now, though, I wonder if I weren’t the nervous one, projecting my sympathetic worries on to her as she got up, confidently introduced herself and her song, and loudly sang into a microphone without a stumble. I know I’m her proud mama, but everyone in that room lapped up her cute persona, fashionable glasses, and memorable lyrics. She killed it!

Afterwards, she ate up the attention, basking in everyone’s comments like, “When can I buy your album?” “I’ll remember this when you’re a big star” and “You are so brave for doing that!” In another couple years, she will unfortunately learn to demur to positive feedback, but for now, I look on proudly at what she accomplished in a few weeks, and I know she has every right to celebrate the accolades. She has a good ear, she has a sense of poetry, and she has a passion for her music that demands others pay attention. Too few compliments are laid at our feet, and even fewer of us feel worthy enough to accept those compliments. We all might benefit from enjoying a confidence-booster when we can get it–something an 8-year-old should help us remember!

Now, fast-forward a week, and I am sitting in a cute dog-themed tavern in northern Los Angeles with my own mother. We are here to meet the son of a man who ran on the Olympic gold-medal-winning team with my grandfather in 1948. I am still a little unsure how we ended up here, but it seems a series of leaps of faith and moments of grace brought us together. At one point Cliff asked me what prompted me to reach out to him, so I shared the engineering of our encounter: I read an obituary in the USC alumni magazine about his dad which led me down the internet rabbit hole to an address for his mom and a subsequent card to share my condolences.

“Are you going to tell him the real story?” my mother interrupted.

“What real story are you talking about? I don’t know what that story would be,” I replied.

And like any proud mother who is half responsible for this hair-brained trip to Southern California, she told our host that I read Louis Zamperini’s book (Unbroken by Laura Hillenbrand) and proclaimed to her that I could write something better. Immediately embarrassed, I protested that I would never have said such a thing because sitting on the precipice of actually beginning to write this thing, I am terrified of the prospect of not…writing…anything, much less a New York Times bestselling book eventually adapted into a popular film. To make matters worse, Cliff laughed at my obvious downplaying of my arrogance and then explained he grew up with Louis Zamperini, Louis gave him his first motorbike, and he sat in front of Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt at Louis’ funeral. Somehow I found the one man who knows the real Zamperini and the writer of his tale–the one man who can dismiss with measurable authority my own attempts at telling my grandfather’s story.

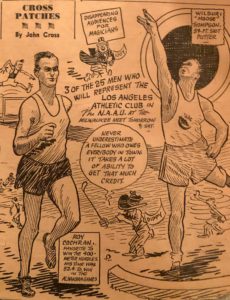

Unlike my daughter, I do not have youthful confidence, bubbling up from the innocence of never knowing the Grace Vanderwaal’s of the world have already “been there and done that.” My foray into writing this book is like trying to remake The Lion King–flashier stars and newer technology doesn’t change the fact the new film will always be second to the original when you’re competing with a nostalgic thirty-something’s cherished memories of a more innocent time. You can’t compete with someone’s first. So, writing about an Olympian who ran for the Los Angeles Athletic Club in the 1940s before ending up in the Pacific during World War II does sound familiar, right?

That might be what is so funny, even ironic, about our trip to California to meet this man’s family. Somewhere in the recesses of my memory, I know I have pursued this story because of the success of Unbroken, because of seeing the parallels between Louis’ experiences and those of my grandfather. Hell, my daughter probably first picked up a ukulele because she had watched Grace’s run on America’s Got Talent.

So where might this realization leave me as I contemplate the prospect of spending years on research, writing, and obsessive questioning whether any of it is good? I suppose I already knew the answer before I sat down to write this post: focus on your ten-year-old self who brought home that IBM Selectric from dad’s work with the intention to write an entire novel over the weekend; focus on you at age twelve when you met your Mississippi family for the first time and recognized how vast and varied your personal history actually was; focus on your 35-year-old version who started small drafts but never showed them to anyone for fear of ridicule; finally, focus on who you are today at 43, the mother of two fearless children, who happened to reach out to a stranger with no real idea of what you might find, but with a glimmer of hope that somewhere in there might be a story.