When I was thirteen, decades before Taylor Swift made it cool, my mom returned from a conference with my junior high theater teacher and told me he believed I was learning but I “didn’t realize it.” His lessons were like sneaky vegetables, steamed and pureed and hidden in the spaghetti sauce so I never knew the nutrition I received. Needless to say, I rolled my eyes, hard, at this theory. I had sent her to talk to him because his teaching methods and general demeanor were weird. Who knows why my mom indulged me except she’d never had a kid who cared about school like this before.

That same school year, I solidified the idea I wanted to be a teacher. Not so I could hide knowledge, but because my math teacher Mrs. Wilhite could stand at the blackboard, writing proofs and formulas, and make me see all I was discovering. Some evidence points to the fact I had wanted to be a teacher as early as 5th grade, but this was the year I could step outside myself as a student and recognize what my teachers were doing, not just for me but for all my classmates, and I wanted to have that kind of power and influence.

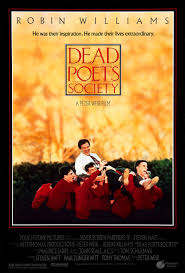

A year later, the film Dead Poets Society and Robin Williams’ Mr. Keating inspired me to become an English teacher.

Fast forward another two decades, my career well established, I found myself spending more time talking to teachers about teaching. At the height of the “evaluation movement” (where everyone believed we could just assess teachers into being great), one of those colleagues, a man who was almost too hip to be a teacher, told me he thought we needed to be more realistic about the quality of the teaching profession. His argument: there are three million teachers in this country; how could they possibly all be great, life-changing, transformational figures in our lives?

In other words, how could we all be Mr. Keatings?

I took offense at the idea. I had been taught by excellent teachers. I had worked with excellent teachers. My children had been blessed with excellent teachers. Of course there were mediocre apples in the bunch, but in a profession like teaching, didn’t most of us come to this like a calling?

Now I sit at the end of Teacher Appreciation Week, my least favorite week of the school year, and I wonder if I’m the only one who got caught by the Cult of the Mr. Keatings. Did anyone else believe they would stand on their desk, spout Romantic poetry, and ignite a generation to make their lives extraordinary? And if my students don’t line up to silently protest my firing (okay, thankfully that’s never happened to me), does it mean I’m not as great as I thought I was going to be at thirteen? If my students don’t shower me with gifts, thank you notes, and promises to visit next year, does it mean I’m not excellent enough to be appreciated?

Let’s hope not.

Today, I want to celebrate the decent teacher. The teacher who gets it done without complaint or fanfare. The reasonable teacher who lets that kid slide because it won’t matter in the grand scheme of things. The teacher who genuinely believed I was learning something, even if I didn’t realize, or appreciate, it at the time.

Not the great teacher, but the good teacher. Try to remember them this week.